Decoding confidence: lessons from the lab

By April Cashin-Garbutt

Confidence comes in many forms. Imagine you are lying in bed, and you think you might smell something burning. While you might not be confident about the smell, you are confident you should get up to check. Research led by SWC Group Leader Dr Jeffrey C. Erlich and NYU graduate student Xiaoyue Zhu set out to disentangle the neural mechanisms underlying these different kinds of confidence.

Confidence: more than a feeling

“You can’t just be confident, you have to be confident about something – whether it’s self-confidence, confidence in a decision, or confidence in a perception,” explains Dr Erlich, corresponding author of a new study published in Neurons, Behavior, Data analysis and Theory (NBDT).

These different types of confidence are particularly evident when the consequences of a decision are asymmetric. In the burning smell example, our perceptual confidence may be low, but our decision confidence is high due to the potential negative consequences of not acting.

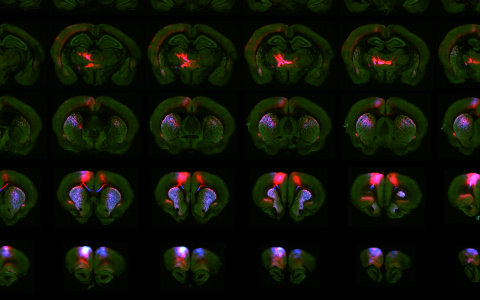

Dr Erlich hypothesised that the posterior parietal cortex (PPC) may be involved in confidence. Previous research has shown that silencing PPC has little influence on decisions, but recording from the area allows you to predict what animals are going to do.

“Many studies on PPC ask people or animals to report their decision and not their confidence. If confidence wasn’t important in the decision process, then silencing PPC would have no effect. Yet if PPC is involved in confidence, this might help explain why it allows predictions. People have reported confidence related signals in primate PPC, but they haven’t tested the effects of silencing in a task that depends on confidence. We’re interested in testing this idea in rodents,” said Dr Erlich.

Designing a task to study perceptual decisions under asymmetric reward

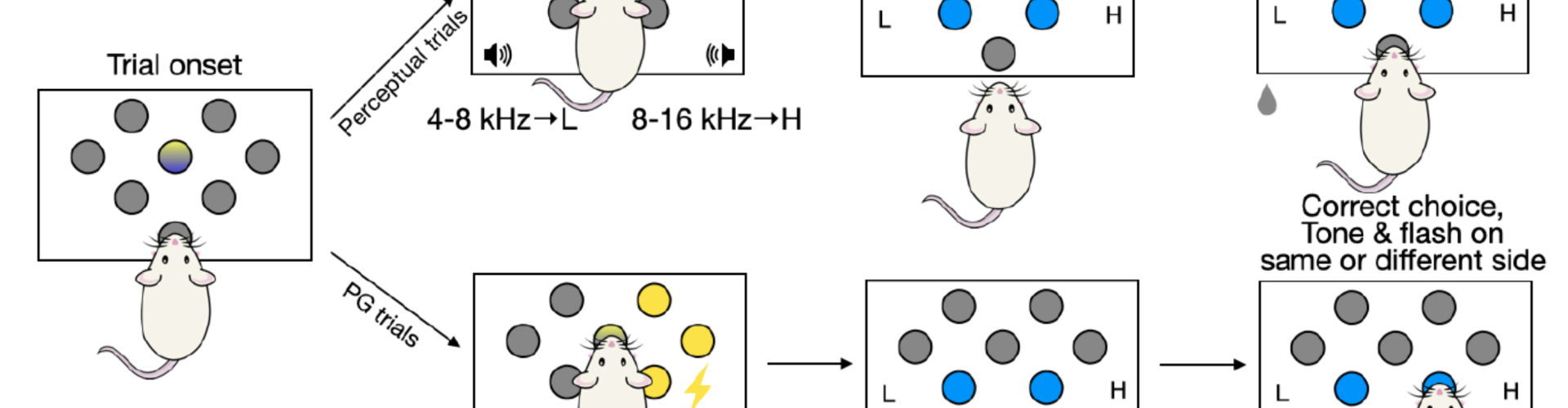

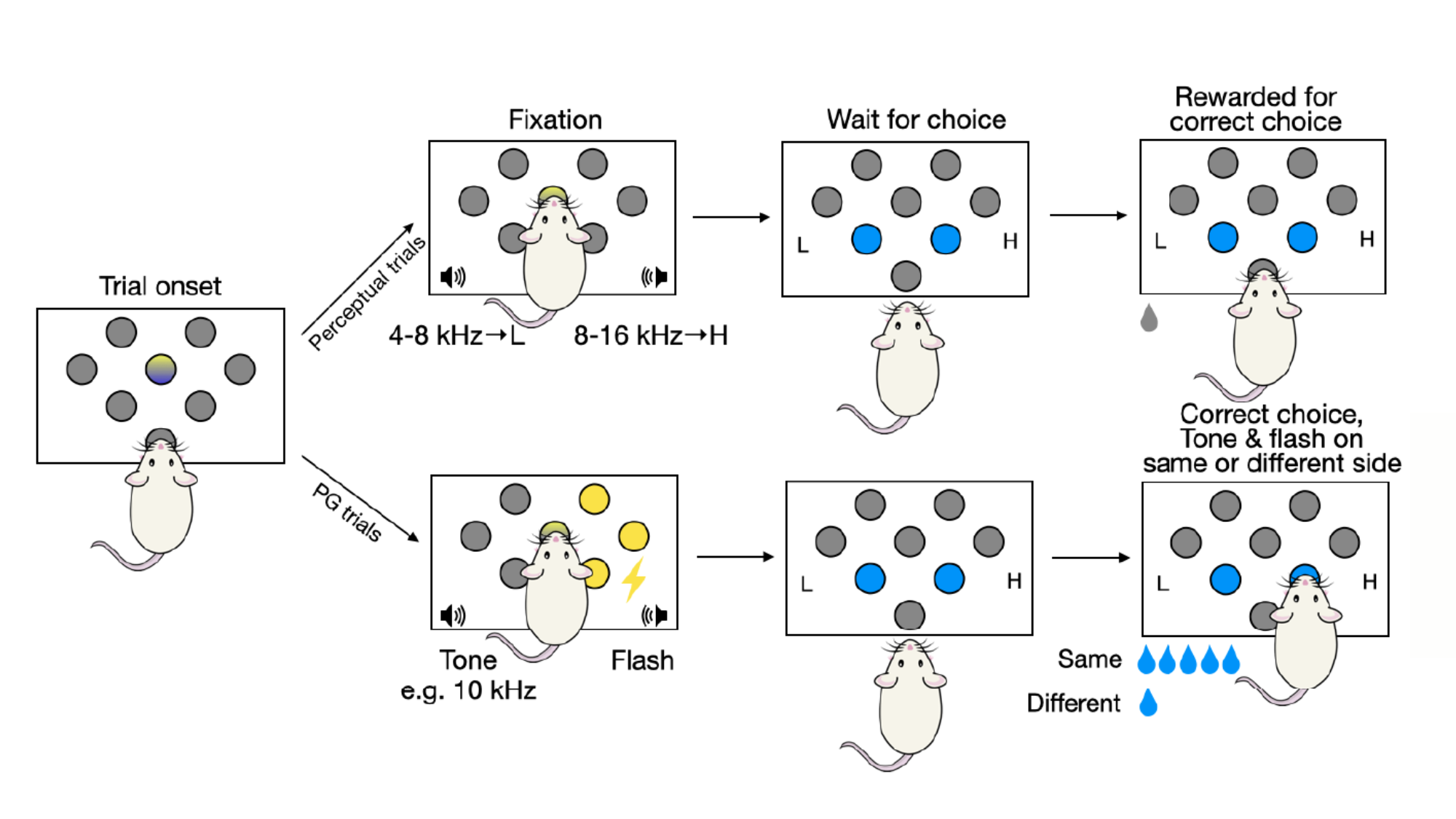

The researchers designed a perceptual gambling task where rats had to integrate their perceptual confidence with economic information on a trial-by-trial basis. The rats needed to report whether a sound was lower or higher pitch than an arbitrary boundary, which was discovered through learning.

On some trials the researchers gave the rats an additional cue in the form of a light on the right or left. The light signalled to the animal that if they respond correctly and to the side of the light, they will receive a bonus reward. However, if they get the answer wrong, they will get nothing.

“If you are 100% sure that you know the right answer, you should ignore the light and just do the correct thing. However, if you have less perceptual confidence in the sound, then you should take into account which side will give the higher reward,” explained Dr Erlich.

Essentially the task creates a lottery with the odds being set by the rat’s perceptual confidence and the outcome set by the light cue. For example, if a rat was 75% confident that the sound was high, it should also take into account the potential rewards of each option.

Imagine the left side is worth 1 reward and the right side with the light is worth 5. Even though the rat is 75% confident that the sound was higher and so it should choose left, it makes sense to choose right as the value of the potential reward on the right (25% of 5 = 1.25) is greater than the expected reward on the left (75% of 1 = 0.75).

“Because of the asymmetry of reward, it sometimes makes sense to respond against your perceptual belief. In the case of a faint smell of burning in your house, you may be confident there is no fire, but you should still check because the consequences of getting it wrong would be very bad. Thus, your decision is sometimes the opposite of your perceptual belief,” commented Dr Erlich.

On the other hand, in cases when there is very low perceptual noise, your perceptual confidence is your decision confidence, because you are sure about the correct thing to do, so you don’t need to consider the asymmetric reward.

Analysing the data

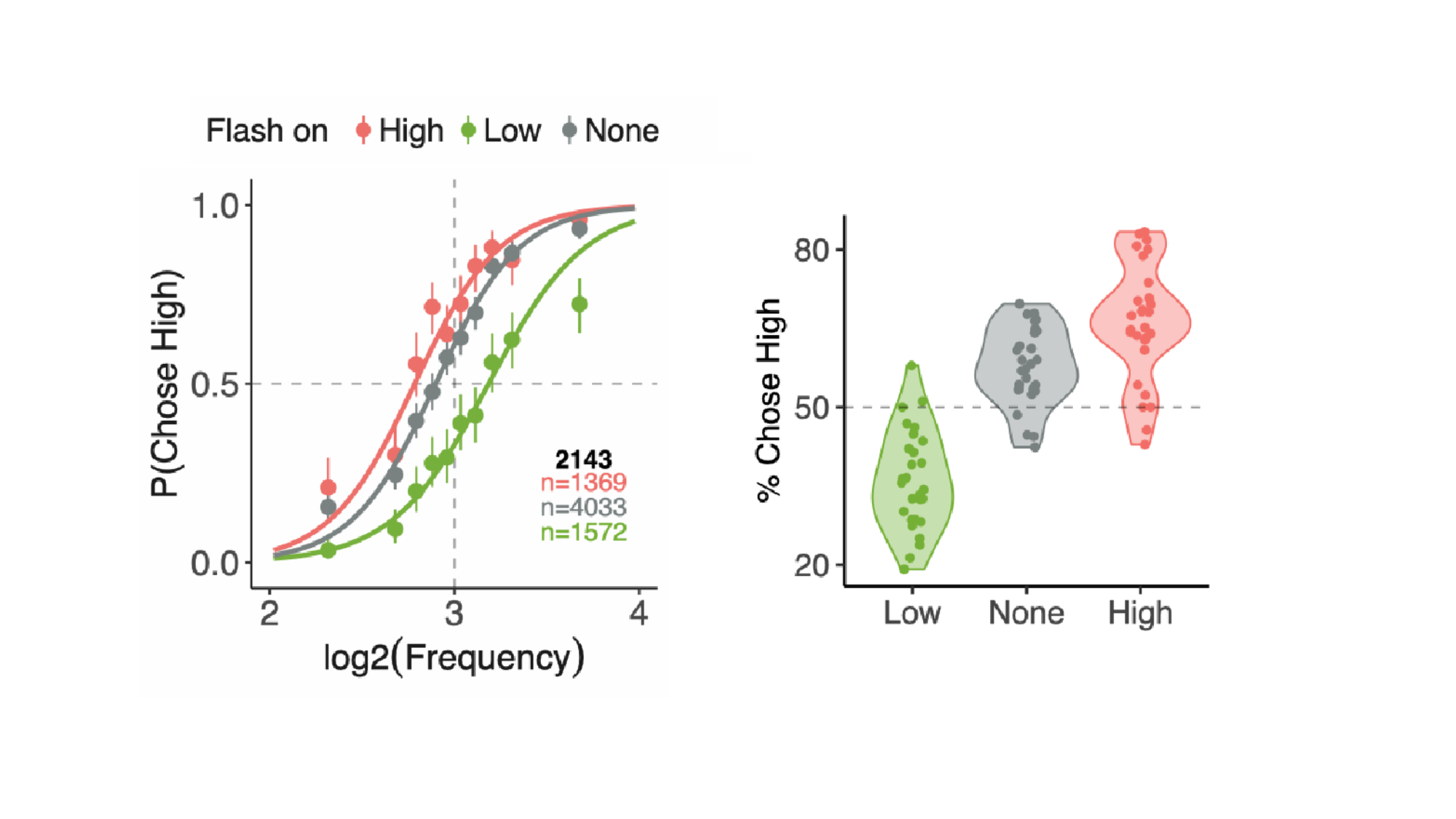

The team used an existing framework called Bayesian Decision Theory (BDT) to analyse their data. They found that the animals they studied weren’t consistent with predictions from BDT, but that the rats did learn to pay attention to the sound and light.

“Our main finding was that rats are able to integrate their perceptual confidence with economic information. They responded more to the high side when the light indicated that they would getter a bigger reward, compared to when there was no light,” explained Dr Erlich.

However, the researchers also found that the rats did not behave optimally in this task. Follow-up analyses showed that individual differences in perceptual noise and risk-tolerance made it challenging to find regimes where optimal integration leads to significant gains in reward.

Learnings from the lab

The team hope that researchers interested in disentangling the different kinds of confidence may be able to learn from this study, and in particular from the task and how they fit the model.

One clear follow-up study would be to inactivate the PPC during the task to determine whether the area is involved in integrating perceptual confidence and economic information. The team recommend making the task harder for all the rats by including more trials near the decision boundary, so that the animals need to consider the reward asymmetry more.

Future studies could also explore the different strategies used by individual animals and how those strategies are updated over time based on confidence in their decisions. This will help further understand how we learn from experience.

Find out more

- Read the full paper in NBDT, ‘A rodent paradigm for studying perceptual decisions under asymmetric reward’

- Learn more about research in the Erlich Lab