Mapping the migratory bird brain

Brain atlases – digital, high-resolution, 3D maps of brain structures – are transforming neuroscience. They improve the ability of researchers to interpret their own data, they enable cross-validation between and within experiments, and they foster collaboration – driving forward studies into learning, memory and navigation, to name just a few.

Now, a new atlas is available, for the migratory Eurasian blackcap. This is the first time a migratory bird brain has been mapped using high-resolution light microscopy. The new resource is freely accessible via BrainGlobe for the neuroscience research community and will advance studies of magnetoreception, migration and navigation.

The new atlas was created by a team from the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre and the University of Oldenburg, Germany. The BrainGlobe team are keen to work with other groups and species experts to create further new atlases, too.

A model for magnetoreception

Every year Eurasian black caps migrate from summer breeding grounds in Europe to winter homes in Africa. They join billions of birds, who migrate thousands of kilometres around the globe. Some travel distances that span from the Arctic to the tropics, and some navigate to within centimetres of their previous locations.

Blackcaps are known to use the Earth’s magnetic field to navigate during their long-distance migrations, and the species is studied as a model for such magnetoreception. To create the new brain atlas, a team at the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre, including experts in the Neuroinformatics Unit worked with researchers at the University of Oldenburg, Germany, who study Eurasian blackcaps and the sensory mechanism that underly magnetic field-guided navigation.

Henrik Mouritsen, a Professor at the University of Oldenburg, is a leading researcher in magnetoreception and part of the project that has created the atlas. Commenting on the new resource, he said; "To me, this is a key tool that the migration, navigation, and magnetoreception community has been lacking for decades. It will greatly improve consistency and comparability between studies and related species and will significantly accelerate our understanding of underlying neuronal mechanisms.”

The new brain atlas has mapped a total of 24 brain areas, including all those known to be involved in sensing and processing information from the Earth’s magnetic field.

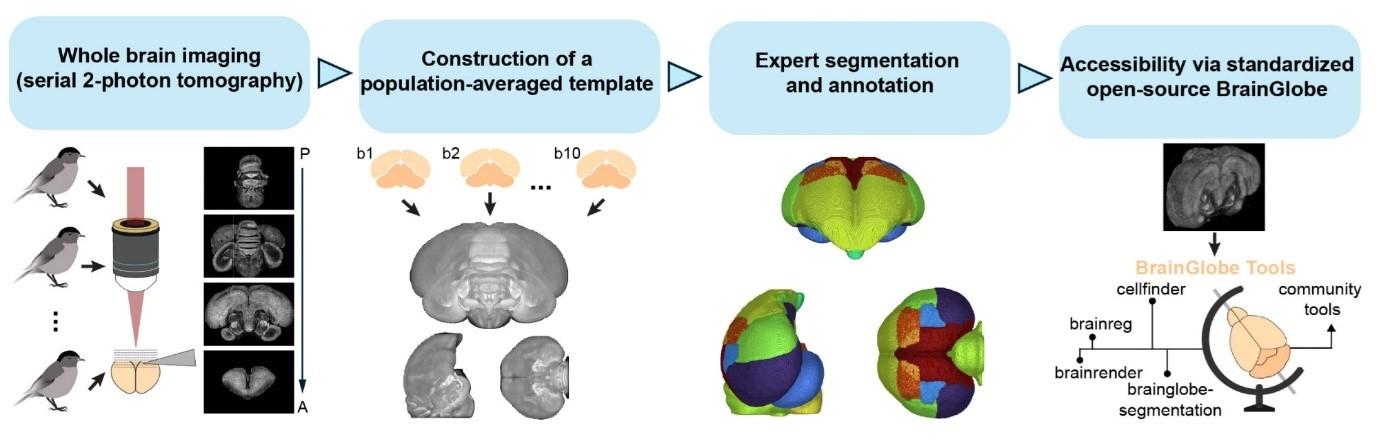

A blueprint for creating brain atlases

Simon Weiler, a postdoctoral fellow in the Margrie lab at the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre coordinated the project to map the Eurasian blackcap. Historically, 2D print-based brain atlases have been used to identify brain areas in different animal species. But this approach hinders the reliable mapping of brain areas, as new data cannot be aligned to precise coordinates. Simon explains; “A digital brain atlas allows the community to directly align their own experimental multimodal data to the common coordinate space of the atlas.”

Being digital also means that the atlas is easier to keep up to date. “A digital brain atlas isn’t a static project. This isn’t a one-person job, and expertise comes from the community. We want people to use and improve the brain atlas resources,” he says.

For Simon, the project is hopefully the first of many, and the SWC team are keen to work with other species experts, too.

“We have documented our processes, the software is open-source, and the hope is that we have created a comprehensive blueprint for the development of any brain atlas in the future.

“As long as you have 3D images of a whole brain, I would argue that anyone can create a brain atlas. The images can be light sheet microscopy, or the 2-photon microscopy images that we used – the method doesn’t matter,” he adds.

Creating an average template

Ten brains were used to create the Eurasian blackcap atlas. Simon used serial-section two-photon tomography in the Advanced Microscopy Facility at the SWC to image the brains, creating well-aligned 2 x 2 x 5 μm voxel size images of entire brains. The Neuroinformatics team then created an average template, combining the data from ten samples. Using an average template means the atlas isn’t biased towards the unique features of any single individual.

“The core aim of BrainGlobe is to democratise computational neuroanatomy. Creating novel atlases is the next step in achieving this. All parts of the pipeline are open-source, and over the coming months we will be improving it so that we, and anyone else, can rapidly create new atlases,” says Adam Tyson, Head of the Neuroinformatics Unit at the SWC and lead of the BrainGlobe Initiative.

The high-quality, spatially averaged brain template was then expertly annotated by the team in Germany to label brain regions common to all bird species as well as those involved in magnetoreception.

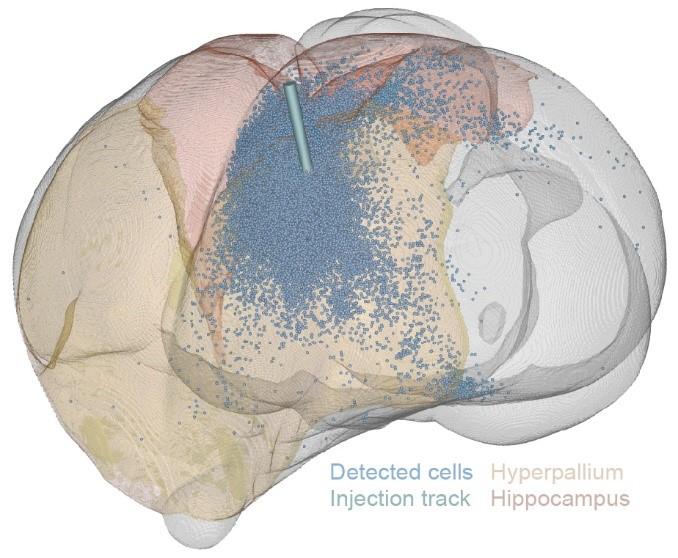

The atlas is available for use within the BrainGlobe system, meaning a wide range of open-source neuroscience tools can be connected to it. To test the usability of the atlas the team ran automatic atlas registration, cell detection and data visualisation on a brain labelled with a viral tracer in the magneto-responsive areas. Their results corroborated previously shown findings, showing how the atlas can be used in practice.

Simon commented; “I hope that this atlas becomes a common reference frame for researchers all over the world, and people can easily map their findings. I hope that people across the community will come to speak the same language when it comes to brain areas.”