Targeting memories as a new therapeutic approach to psychopathologies

An interview with Professor Karim Nader conducted by April Cashin-Garbutt, MA (Cantab)

Professor Karim Nader, McGill University, recently gave a seminar at the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre on specific impairments of consolidation, reconsolidation and long-term memory that lead to memory erasure. I caught up with Karim to find out more about his research and the clinical implications of targeting reconsolidation.

Please can you outline the process of memory consolidation and explain how our understanding of the phenomenon has changed over recent years.

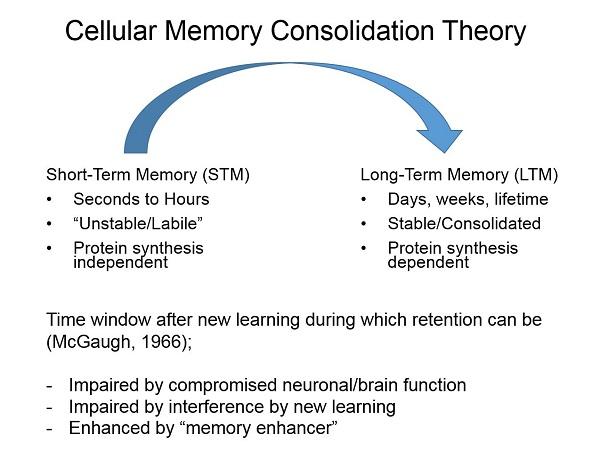

The traditional idea of memory is that new information is not wired into your brain immediately, it takes a couple of hours to be consolidated.

A good example of this is if you are talking to someone at a party and they give you their name but someone distracts you, the probability of forgetting the information is higher.

It used to be thought that once a memory is wired into the brain, it is always consolidated. And so memory consolidation was thought to be a one-way process, i.e. once a memory is wired into the brain, there is no way out.

However, we know that every time people recall memories and talk about them, they can modify the content of those memories.

How do you define the evidence on which reconsolidation is based?

Reconsolidation is simply defined as a time-dependent process in which, during retrieval of an existing memory, the memory is un-stored from the brain and must be restored over time. The concept arises from experimental observations that established memories during recall are labile in similar ways to new memories during the consolidation period.

The lines of evidence for reconsolidation are the same as those for consolidation. Everything can happen within the time course, while the memory is being wired into the brain. So if you interrupt someone and reactivate a memory, for example by asking them the name of the person they spoke with, the reactivated memory is vulnerable and can be altered or degraded.

This is an interesting phenomenon, which many people are trying to apply in a clinical context. For example, you can make memories stronger, and you can also functionally erase mechanisms in a memory-selective manner. This is because our memories are not snapshot pictures in the brain, every time you call them up they can be modified over time.

What are the potential clinical implications of reconsolidation?

The mechanisms of the synapses of memories undergo the same mechanisms as synapses of psychopathologies. Take for example a child with obsessive compulsive disorder, each time the child experiences the compulsion, the neural representation become transiently unstored and, theoretically, if you have a compound to block reconsolidation, then a one session intervention can provide therapeutic benefit.

This can also be done with phobias and people have shown that you can erase phobias after a two minute traumatisation experience followed by a compound that blocks reconsolidation, which reverses the phobia.

People have shown that smokers can be stopped from smoking as they can reverse their memory by targeting reconsolidation which can impair the cravings of smoking and even opiate addiction.

Theoretically, talk therapy could also be used. For example, a patient with anorexia could be presented with their trigger, such as food, and the memory could be updated such as that food is good for you, after a single intervention.

Furthermore, non-pharmacological talk therapy has been shown to be more effective in PTSD than pharmacological therapy, after a couple of sessions.

What are the advantages to developing therapies that influence memory reconsolidation as opposed to targeting other aspects of memory formation or retrieval?

Targeting memory retrieval is very difficult as you need a selective mechanism to inhibit a specific memory. The beauty of targeting memories during reconsolidation is that we can block the emotional aspect of a particular memory. The problem with targeting memory formation is that you just never know when traumatisation is going to occur.

How far away are we from using memory reconsolidation therapies in humans and what are the main challenges that will need to be overcome?

People have been developing memory reconsolidation therapies and it is amazing what has already been published in JAMA and other journals. What needs to be done next is to further improve public education around mental health as stigma still remains.

About Professor Karim Nader

Dr. Karim Nader obtained his Ph.D. from the University of Toronto in 1996. Following his Postdoctoral studies at New York University, where he worked under the supervision of Dr. Joseph LeDoux, he obtained his current position at McGill University.

Since then he received numerous awards and honors including being selected for the “Canadian Top 40 under 40” in 2005, as well as part of Canada’s “Who’s who?” in 2010.