From a systems neuroscience PhD to a postdoc in visual research

An interview with Alex Fratzl, Postdoc, Roska Lab, Basel, formerly a PhD student in the Hofer Lab at SWC, conducted by April Cashin-Garbutt

How did you decide what to do after your PhD at SWC?

My goal is to pursue an academic career to advance neuroscience as a principal investigator in the future, so the next logical step after the completion of my PhD was to apply for postdoctoral positions. After very exciting discussions with Prof. Botond Roska and members of his group, I decided to join the team at the Institute of Molecular and Clinical Ophthalmology (IOB) in the beautiful city of Basel.

Why did you choose to join the Roska lab?

The Roska laboratory is a pioneering research group, using and developing groundbreaking and interdisciplinary circuit neuroscience methods to investigate the visual system. Over the course of the last two decades, the group has discovered fundamental properties of neural circuits using a combination of physiological, molecular, viral, behavioural, and computational approaches.

A main goal of the laboratory is to understand visual perception. Research within the laboratory is therefore very well aligned with my personal scientific interests, as I am passionate about how the brain processes sensory stimuli and how experiences, emotions and internal mental states influence sensory information processing. Moreover, what was really appealing to me, is that the group is embedded within the IOB, where basic researchers and clinicians work hand in hand to advance the understanding of vision, its diseases and to develop new therapies for vision loss.

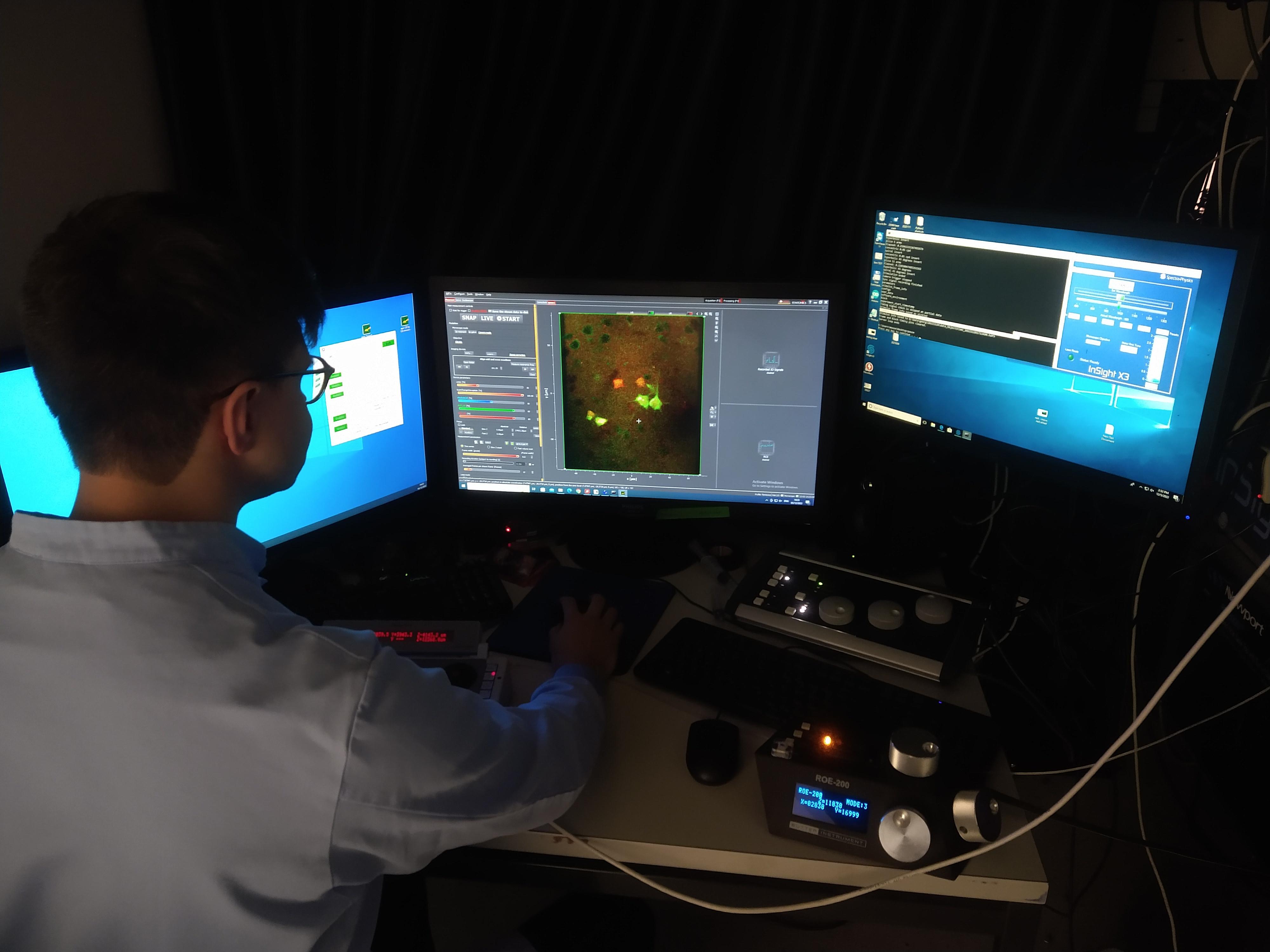

Image of Alex Fratzl in his new role as postdoctoral researcher in Botond Roska’s lab at the Institute of Molecular and Clinical Ophthalmology Basel, working on the question of sensorimotor processing in the early visual system of rodents.

What does your role as a Postdoctoral research fellow involve and how does it differ from being a PhD student?

As a postdoctoral research fellow, I design and conduct experiments, analyse and interpret data and finally disseminate my findings through presentations at conferences and peer-reviewed publications. Overall, the main tasks are quite similar to the ones I had before. Personally, I did not experience an abrupt fundamental change between being a PhD student and a postdoctoral researcher. However, this might strongly depend on both one’s predoctoral and postdoctoral experience.

I think that most people strongly evolve during their PhD as they become more senior and independent. While at the beginning most PhD students can feel overwhelmed by a possibly new work setting, towards the end of their experience they are significantly more confident and start supervising more junior lab members themselves. Therefore, it is not unusual that senior PhD students often have even more responsibilities than junior postdocs in a lab, since the latter need to get used to a completely new environment and need to learn once again new scientific skills.

Honestly, starting a postdoc felt to me a bit like starting a PhD. However, the learning curve is much steeper, given that many skills I acquired during the PhD are actually transversal and help me progress faster in the new environment. After a few months, I felt I was reaching a greater level of scientific and intellectual independence than during the later stages of my PhD.

There are also some more practical differences. For example, I spend much more time applying for fellowships and writing grant applications than before, so I get exposure to the more administrative part of science, where one needs to think more seriously about funding. This is very helpful in the longer term for those who are looking to become independent, given that these applications force one to think projects through and ahead of time, in a more holistic manner than would usually happen during a PhD.

Moreover, thanks to the skills acquired during the PhD, I feel more qualified to mentor more junior scientists in both scientific and career development matters. Nevertheless, the day-to-day science as a postdoc is not fundamentally different to the one of a PhD student.

What are the main areas of research you now focus on?

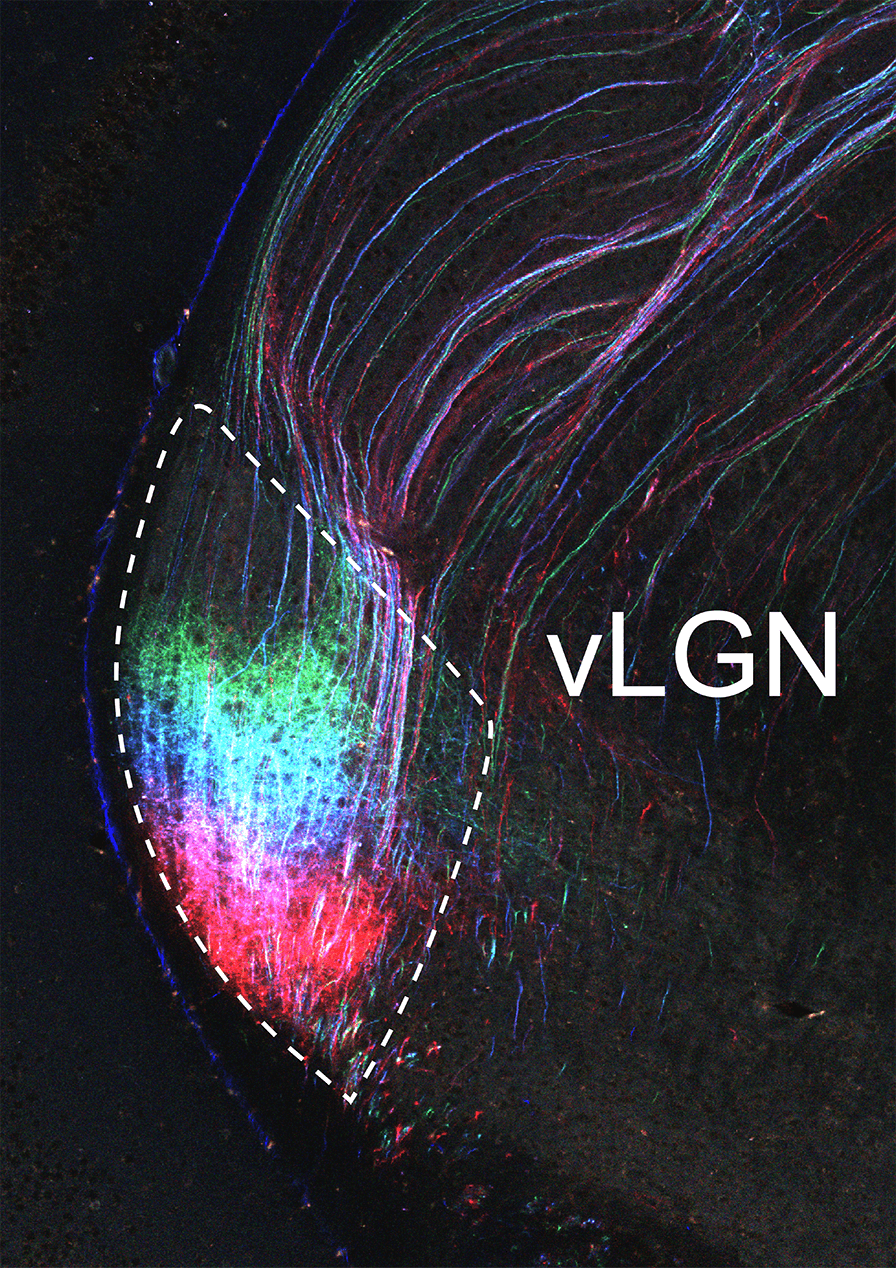

During my PhD, which I carried out in Sonja Hofer’s lab at the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre, I investigated the function of the ventral lateral geniculate nucleus (vLGN), an inhibitory prethalamic area in the visual system, which has so far not been extensively studied. We identified it to be a critical node for the control of defensive responses evoked by visual stimuli. This work, I believe, strengthens our understanding of neural circuits underlying behaviours critical for survival.

Image of the ventral lateral geniculate nucleus (vLGN) with axonal projections (inputs) from different positions in the visual part of the cerebral cortex labelled in different colours.

During my postdoc, I will continue working in the early visual system of rodents, however addressing the fundamental question of sensorimotor processing. I am interested in understanding how specific visual information coming from the retina is transformed and used within different brain regions to ultimately drive a motor action.

How did your PhD help equip you with the skills and knowledge needed for a career in neuroscience research?

The training I received at the SWC and in the Hofer lab was excellent. Given my goal of opening my own independent research lab in the future, the experiences during my PhD helped me to develop scientific, intellectual, and transversal skills needed for succeeding in an academic career.

Moreover, I learned many cutting-edge neuroscience techniques such as calcium photometry, electrophysiological recordings, and optogenetic and chemogenetic manipulations in freely-moving animals. This set of skills will allow me to address some of the most interesting questions in systems neuroscience. Moreover, the highly collaborative nature of the institute, where PhD students benefit from a generous access to both immense physical and intellectual resources, makes it an exceptional environment, in which I was very privileged to be immersed.

Fundamentally, during my PhD at the SWC, I learned much more than just methods and techniques; it was about learning a way of thinking. I gained an understanding of how to get started working on challenging, but stimulating problems. This is often not something taught during our undergraduate or master’s degrees as these tend to be more knowledge-oriented. In research, what matters in the end is to phrase a question that is both interesting and also something you can realistically address.

While leaving my comfort zone in this regard was undeniably difficult, I am immensely grateful for Prof. Hofer’s mentorship and the rigorous training provided within the lab. On a personal level, I also greatly benefited from the experiences during the PhD as I learned to overcome difficult challenges - especially during the covid-19 pandemic.

Before you started your PhD, did you always want to have a career in academia?

During my undergraduate and master’s degrees at EPFL, I became very interested in neuroscience, as it is at the intersection of many different scientific disciplines such as biology and physics. In the end, the brain might determine who we are as a person and lays the foundation for all human accomplishments, for the better and for the worse. I feel privileged to be able to contribute to our understanding of fundamental principles of brain function.

While most people - myself included - would agree that academic research has its challenges, I still feel that the freedom of thought and the questions you can address make it worth pursuing a career in academia. In the long run, I would really enjoy being able to run my own research programme as a principal investigator, to contribute to our understanding of brain function and - hopefully - to make academia a better place for everyone.

Looking back, what would you say was the most important thing you learnt during your PhD?

It is difficult to pick a single most important thing I learnt during my PhD, as there were quite a few that I consider crucial for both my future career and my personal development. It might sound cliché, however, I believe that in the end you learn even more about yourself than about your actual research topic.

For me, also given the very challenging period of the pandemic, resilience as well as learning how to dedicate the right amount of energy and brain power to a specific task were critical. I also learnt the importance of finding the right compromise between being excited about my own work and being able to emotionally detach myself from it. I think finding the right balance in this regard is crucial. I am usually very excited about anything I am working on, however, identifying too much with the outcome of your own work can come with great danger with respect to mental health and personal wellbeing. Putting things into perspective, realising what real priorities you have in life, can actually help you do better work and succeed in a happier way in academia, or in any other highly competitive job.

Have you stayed in touch with many people at SWC and GCNU?

Yes! Overall, I had a great time during my PhD and stayed for a total of four and a half years in London, so I made many good friends at the SWC and GCNU, with whom I am still in touch. Moreover, I am still involved in different projects within my former lab and talk to Prof. Hofer and other lab members on a regular basis. Also, given that I continue working in a similar scientific field, I regularly meet scientists from the SWC at international conferences.

What are your future career plans?

My long-term goal is to establish my own independent research group, in which I would like to study the neural mechanisms underlying subjective sensory perceptions and their contributions to decision-making. For the time being, I would like to progress with my postdoctoral research and then apply for independent positions once the time is right.

What advice would you give to someone deciding what to do following a PhD in neuroscience?

During their PhD, many researchers ask themselves whether they want to stay in academia or not. However, given that postdoctoral researchers and PhD students usually work closely together and their day-to-day work is quite comparable, most PhD students gain a relatively clear understanding towards the end of their training of how it would be to be a postdoc and whether they would like to pursue an academic career at all. This is in stark contrast to undergraduate or master students, who usually have less experience working in a lab environment and therefore do not really know what to expect from a PhD.

On the other hand, most PhD students have virtually no idea about all the interesting job opportunities that exist outside of academia, given that the main focus of most PhD programs is to lay a foundation for a career in academic research. I would therefore strongly encourage everyone - and particularly PhD students who are unsure whether to stay in academic research - to get some experience and exposure outside of academia as early as possible during their PhD training. This includes internships in the private or public sector, discussions with former PhD students who have left academia and attendance of diverse workshops targeting PhD students interested in alternative career paths. Gaining deeper insight into both worlds will be strongly beneficial in choosing the right path for yourself.

About Alex Fratzl

Alex Fratzl is a postdoctoral researcher in Botond Roska’s lab at the Institute of Molecular and Clinical Ophthalmology Basel, working on the question of sensorimotor processing in the early visual system of rodents. During his PhD in Sonja Hofer’s lab at the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre he studied the role of the ventral lateral geniculate nucleus in visually evoked escape behaviour. Born in Vienna, he studied at EPFL in Switzerland and carried out his Master’s thesis work in the Andermann lab at Harvard Medical School. He is interested in how the brain processes sensory stimuli and how experiences and internal mental states influence sensory information processing.