Animal emotions and empathy

An interview with Professor Frans de Waal conducted by April Cashin-Garbutt, MA (Cantab)

Professor Frans de Waal, Director, Living Links, Yerkes National Primate Research Center, Emory University, Atlanta, USA gave the annual SWC lecture this year on animal emotions and empathy. I caught up with him afterwards to find out more about his research.

Setting up for Professor Frans de Waal’s lecture in the SWC seminar room.

How do you define emotions and in what ways are they distinct from feelings?

Emotions are states of body and mind. The body is often forgotten by psychologists as they focus more on feelings when they interview and survey people.

Emotions are bodily states in response to the environment, for example changes in your blood pressure, temperature, heart rate and so forth. When people describe their emotions, they often use very visceral language, for example talking about their stomach or their heart. There are many gradations of emotions but the basic ones are fear, anger, love and so forth.

Feelings are more of a subjective evaluation and that’s only a part of the emotions, as not all emotions reach the feeling stage. Feelings involve both experiencing emotions and also then interpreting them.

The feeling stage is much harder to get a hold of and that has often been used against the idea of animal emotions as people have said: we will never know what animals feel. This is probably true, however, we may be able to determine something called ‘valence’.

Feelings have two dimensions: one is arousal, how strong or weak the feelings are, and the other is valence, whether they are positive or negative. We can probably measure both of those dimensions in animals as we know whether their experience has been positive or negative, as they change their behaviour accordingly. So we can get a little bit of a handle on the feelings of animals but we will never know exactly what an animal feels.

Why has there traditionally been a taboo around the scientific study of emotions?

This is almost entirely due to the behaviourists in America, who at some point decided we can only work with observables and that we shouldn’t be talking about unobservables. They had a very mechanistic view of animals, where everything that animals do was thought to be learnt from experiences, both positive and negative.

My problem with that view is that science is full of unobservables, for example, we talk about models like evolution, continental drift, theory of mind, even though we cannot observe them. With all of these things, we take scientific indicators to suggest whether something has happened. We should be doing the same thing with feelings and emotions: the fact that you cannot observe them, doesn’t mean you cannot postulate them.

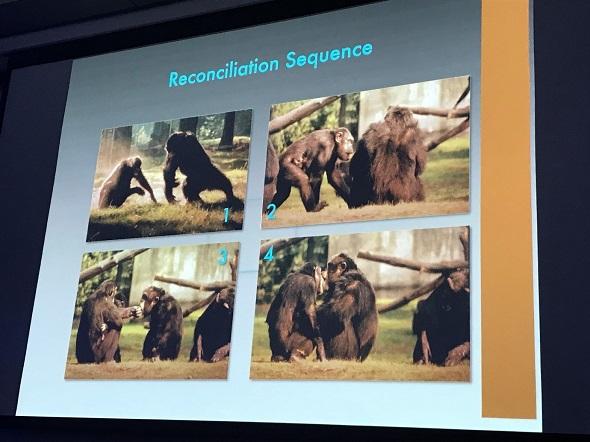

Professor Frans de Waal showed how chimpanzees kiss and make-up after a fight.

How has this taboo hampered animal research in this area and why is the view now outdated?

There was also a taboo on cognition, and thinking in animals, and over the last 25 years we have certainly seen a revolution in cognition research. As a result, behaviourism has lost its grip and now there is a revolution coming on animal emotions.

This revolution is partly driven by neuroscientists, as if you study fear in the amygdala in rats and you extrapolate to fear in humans, you are assuming that it is the same sort of emotion going on.

So neuroscientists have broken down the taboo to some degree and people who study animal behaviour are also less reluctant to talk about the emotions of animals.

Why is the study of animal emotions a necessary complement to the study of behaviour?

Because emotions organise behaviour. Think about understanding the responses to the state of fear, such as trembling or trying to escape. Fear goes together with appraisal of the environment and stimuli, so that you come up with the right response.

For example, if a monkey sees a snake in the grass, it needs to get up into a tree, however, if it sees a bird of prey, getting into a tree might not be the best response. Animals need to evaluate their best response, given the circumstances, so it is a combination of cognition and emotion and that organises behaviour.

I don’t think we are going to understand animal behaviour without emotions, because emotions are the principles behind behaviour.

Professor Frans de Waal discussed homologies such as the hands of a human and a chimpanzee.

How far has our understanding of the expression of emotions in face and body language advanced since the work of Darwin?

There has been a lot of good work on facial expressions. Darwin only scratched the surface and now we even have studies on facial expressions in mice. For example, mice show different facial expressions when they are in pain than when they are not, and other mice can recognise that. There is even a similar rat study.

Rodents don’t have a lot of facial expressions in comparison to primates. It used to be said that humans have far more facial muscles than chimpanzees because we need a greater variety, but recent anatomical studies have shown that the chimpanzee has exactly the same muscles in the face as the human does, so we must assume the chimpanzee has an array of facial expressions, sometimes very subtle ones.

There is a lot of facial research as we often work with touch screens, so we can show monkeys and chimpanzees faces up on the screen and let them choose between them. There is a lot of progress that has been made in this area. There is also a new technique called eye-tracking that allows us to see which parts of the face the primates are looking at, which parts are important to them.

A baby gorilla laughing as it is being tickled.

Do you think we are smart enough to know how smart animals are?

I’m an optimist, so I think we are able to know how smart animals are. However, we need a bit more humility and less focus on the human to achieve this. A lot of the studies of animal intelligence have taken a very human-like perspective. For example, when elephants were tested to see if they could use tools, people assumed that the elephant would pick up a tool and use it, just using their trunk instead of a hand.

And so, they did an experiment where they put a piece of food outside of the enclosure and gave the elephants a tool to see if they would reach the food. The elephants didn’t do anything and people concluded that elephants couldn’t use tools.

But then a different team set up another test where they hung food very high and gave the elephant boxes they could move. They found that the elephants moved the boxes so that they could stand on top of them to reach the food. So they were using a tool, but they were not willing to use their trunk.

The thinking behind this is that the trunk is not just a grasping organ for the elephant but also a smelling organ and the elephants didn’t want to shut it down by putting a stick in it.

And so if you extrapolate from human behaviour to elephant behaviour, you need to take into account that it is a different body in a different animal, so there are different rules.

This is not so much a problem with chimpanzees as their bodies and outlook on life are very similar to humans, but if you test an octopus or a bird, you have to follow very different rules of engagement.

One of the issues in the field of animal cognition is people getting negative results and drawing big conclusions, however, negative results often mean very little.

An elephant looking at a mirror to see the inside of her mouth.

What impact do you think machine learning could have in this field?

Machine learning is based on similar principles in terms of positive and negative experiences. There is even a field of machine emotions, where people try to give robots emotions partly to enable them to interact with people and read the emotions of people.

Another reason is because emotions organise behaviour. The experts understand that to get the robots to react in a way that we understand, the robots need to have these emotional states.

There are already robots in a lab in Portugal that play chess with children. The robot looks like a person and sits on the other side of the chess board and reads the faces and interprets the tone of voice of the child so that they can respond accordingly, for example by showing sympathy or being competitive, depending on how the child responds.

What do you think the future holds for the study of animal emotions and empathy?

We have only just begun working on empathy and it is a big topic in human studies too. Emotions in general is the future of animal behaviour research, because there has been a taboo on emotions for so long.

I think we can reinterpret a lot of what we do in emotional terms, so I see a great future. For example, animal studies may help us to understand why certain emotions evolved.

When we wrote on fairness for the first time in monkeys, no one had even thought that the sense of fairness could have an evolutionary basis in other species. Philosophers had made fairness such an abstract topic that could only be explained by reasoning and logic in their minds and so that’s why there was so much resistance initially over the idea that monkeys could have a sense of fairness.

Now that we have the data and people are starting to explore it, we can start to think about what are the advantages of fairness, why would you have that. Then you get a more functional line of thought about something. Instead of just establishing that humans have a sense of guilt, fairness or justice, the question now becomes: how did that evolve, what is it good for, what does it do?

The sense of fairness is based around the emotion of envy, especially related to cooperation. For example, if we have done something together and you got something more than me, I would be envious.

Envy, in my view, is at the basis of fairness. However, not all agree, for example the philosopher John Rawls wrote a book on the sense of fairness where he purposely left out the emotion of envy, as he saw it as a primitive emotion. Thus Rawls tried to explain the sense of fairness solely based on logical principles and why we should do this and not do that.

In my view, I don’t see why you would have a sense of fairness without envy. Why would society care about fairness, if people weren’t sometimes envious of others? If we had no envy at all, why would we worry that someone has a little more than us? I think emotions need to be at the core of the discussion.

Do you think primate research will continue in the US in the next 10 years?

Monkey research will continue in the neurosciences, biomedical, behavioural and so forth, but chimpanzee research has more or less stopped. The National Institute of Health (NIH) has said that they don’t want to fund any more studies on chimpanzees.

Chimp Haven, the chimpanzee sanctuary for chimpanzees no longer involved in research, is growing rapidly as we are taking in another 300 chimpanzees and we already have over 200. The problem of where to house these chimpanzees will at some point disappear though as no more breeding is being done. However, chimpanzees live for a long time (~40-50 years) so for the coming years we need a solution.

What advice would you give to neuroscientists studying animal behaviour?

I am always struck by how much better neuroscientists are at neuroscience than behaviour. Since I am a behavioural scientist and not a neuroscientist, I always look for the behavioural measures that researchers use and sometimes they are interesting and sophisticated but often they are extremely simplistic like activity level, do they go into a dark hole yes or no, and that is not behaviour I find interesting.

For example, rats are such highly evolved social animals with so many subtleties to their behaviour. I worked with rats as a student long ago and they are very cooperative. Just to measure their activity level, or whether they sit on certain platform, yes or no, or do they remember where a platform is etc. is very stressful testing and, in my mind, it is not very informative as it doesn’t really tap into the richness of a rat’s life.

So I feel that neuroscientists often need a lot of training in behaviour. They have very good training in the neural aspects, but they could benefit from classes in animal behaviour to learn how to observe.

The same is true in the Netherlands, where researchers often have a background in neurobiology but not ethology or animal behaviour.

Cover of Professor de Waal's latest book, Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are?

Where can readers find out more information?

- For more information on Moral Behaviour in Animals

- His latest book is Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are?

- Living Links – Center for the Advanced Study of Ape and Human Evolution

- For more information on Chimp Haven

About Professor Frans de Waal

Dr. Frans B. M. de Waal is a Dutch/American biologist and primatologist known for his work on the behavior and social cognition of primates. His scientific work has been published in journals such as Science, Nature, Scientific American, and outlets specialized in animal behavior.

His popular books – translated into over twenty languages – have made him one of the world’s most visible primatologists. His latest book is Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are? (Norton, 2016). De Waal is C. H. Candler Professor in Psychology, Director of the Living Links Center at Emory University, and Distinguished University Professor at Utrecht University. He is also a member of the Board of Directors at Chimp Haven.

He has been elected to the (US) National Academy of Sciences and the Royal Dutch Academy of Sciences. In 2007, he was selected by Time as one of The Worlds’ 100 Most Influential People Today.