Bridging senses and disciplines

Our brains are constantly processing an ever-changing multitude of sensory inputs from our environment. Integrating this information is essential for learning, memory, and shaping our behaviour.

In a recent SWC seminar, Dr. Jan Gründemann, a group leader at the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE), shared his work on the role of the auditory thalamus. Previously viewed as a switchboard relaying sensory information to higher brain areas, his research reveals an additional role for this region in processing complex sensory information during learning.

His work combines state-of-the-art circuit neuroscience tools like opto- and pharmacogenetics with single and two-photon imaging techniques, as well as artificial intelligence, to reveal frameworks of neuronal coding and plasticity in deep brain areas.

In this Q&A, Dr. Gründemann discusses his work and career.

You work at the DZNE, an institute focused on researching causes, preventions and treatments for diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. What brought you there, and how does your research fit into the institute?

With the brain, the challenge is that, beyond halting disease progression, you also need to regenerate lost functions. For instance, in cancer, removing a tumour often results in successful treatment. But in the brain, a big question is how we restore and repair damaged networks.

In Alzheimer’s, that might mean recovering lost networks for memory formation, for example. While the new Alzheimer’s drugs will help to slow the progression of the disease – they can’t undo the damage to the brain that has already been done. So in the long run, we will need a two-step process, where neural networks are retrained and people can recover their memory networks.

Research to achieve that goal is multidisciplinary. And that’s what drew me to the DZNE – it is a really exciting place to work.

At the Institute, people come together from all kinds of backgrounds, from neuroscience, epidemiology, psychiatry, computer science, health care research and many more. And everyone is tackling neurodegenerative diseases. Seeing patients visiting the Institute, the cooperating clinics or taking part in cohort studies, is a powerful reminder of why we do this work.

My group works on how mice form and store memories in neuronal circuits and larger networks. Being at the DZNE, where everything is integrated, means that this understanding might hopefully help us treat patients one day.

What first got you interested in sensory inputs and their integration, memory and learning?

It was a long journey! I started studying biology because I was really fascinated by genetics. Then, during my Master’s degree, I worked on gene expression in Parkinson's disease. We did single-cell gene expression studies, with laser capture microdissection, on the brains of Parkinson's disease patients. This was really amazing and I was totally fascinated.

I felt that those experiments just showed us a snapshot, though, of the brain at a single moment. I wanted to study how neurons generate activity and then get disturbed and perturbed by diseases over time. That interest brought me to London for my PhD at UCL, where I studied how neurons generate signals and how signals are propagated along axons.

It was during my postdoc that I moved towards learning, and the amygdala – which changes activity during learning. This brought me to the question of how we integrate complex inputs from our environment.

Now, my research aims to understand how sensory inputs are integrated, how they are formed into memories, if they're predictive of a good or bad outcome, and which brain networks, neuronal circuits and cell types are part of that.

Could you describe your recent findings on the role of the sensory thalamus in learning?

The key question we are trying to address is how large networks of neurons in different brain areas integrate inputs from the environment. We’re interested in how memories are formed, stabilised and forgotten.

To investigate this, we study the thalamic brain areas – where recent discoveries more and more highlight their importance for adaptive behaviours. But the role of thalamic brain areas in learning across different senses hasn’t been well understood.

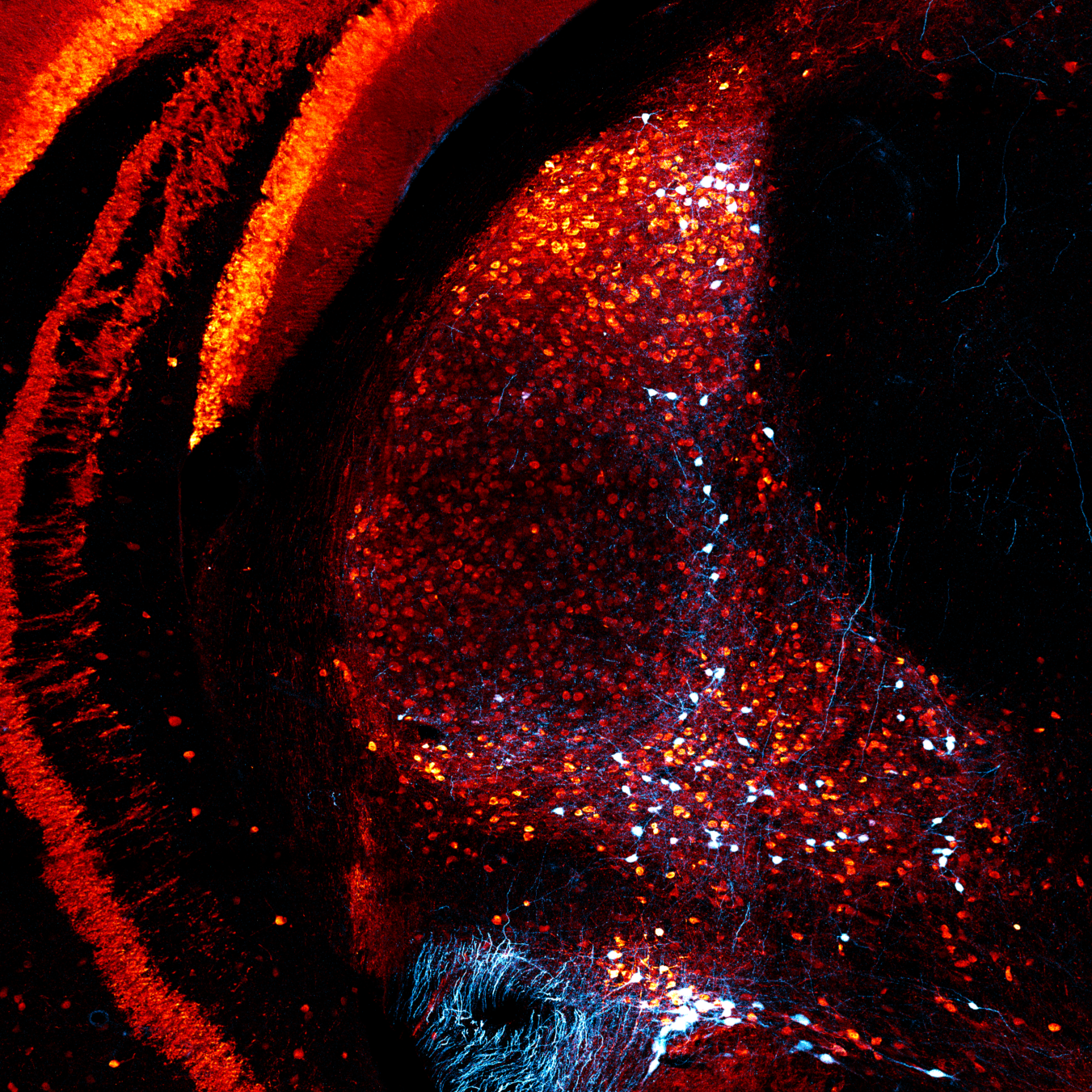

To address this gap, we designed a reward-based learning task for mice that incorporates multiple senses. During the task, we visualised deep brain regions using two-photon calcium imaging of large populations of auditory thalamus (medial geniculate body, MGB) neurons.

We found that MGB neurons focus on reward predictors, regardless of the sense involved. Different classes of MGB neurons became active during distinct stages of the task and specific outcomes. During non-sensory delays in a task, MGB neurons formed coordinated patterns linked to predicted outcomes.

This showed us that the auditory thalamus flexibly processes cross-sensory information during learning and plays a key role in complex behaviours.

Were you surprised by your findings that the auditory thalamus has a role in adaptive behaviour?

We were expecting some plasticity in parts of the thalamus based on our previous work, which is often just been regarded as a relay of sensory information from the periphery to cortical areas.

What was striking was that we saw that these cells are changing their activity patterns in a learning-dependent fashion. This suggests the auditory thalamus is far more than a simple switchboard – it actively adjusts its outputs and modulates the information delivered to the cortex and other brain regions. These computations appear to be directly relevant for changes in behaviour and potentially for shifts in perception.

What was also striking was that the changes in responses to sensory stimuli we observed primarily occurred through the dynamics of individual cells. In contrast, the broader network representation remained quite stable over time. This is markedly different from limbic structures like the amygdala, where network dynamics are more fluid in response to learned stimuli.

This reveals a dual role for the thalamus. On one hand, individual neurons adapt their activity patterns to guide learning. On the other, the network as a whole provides stability, supporting reliable sensory perception. We believe this balance is critical for integrating learning with consistent sensory processing.

Why is it so important to understand these circuits?

We became deeply interested in this because we believe that memory is not confined to a single cell. If a single cell were to hold a memory, losing that cell would have devastating consequences – and brain cells do undergo some turnover.

Instead, we think that memory resides within distributed neural networks, which serve as both the source and storage of information. To truly understand this, we need to study these networks over time, observing how their activity changes during the process of learning.

What's the next piece of the puzzle that you're working on?

Decisions on my research direction come from the type of work I've done. I’ve gone from genes all the way up to changes in patterns of activity in neural networks.

For our next steps, we're probably going to align network activity with changes in gene expression. Essentially coming full circle.

We will focus next on how the changes in plasticity that we observed in those networks are guided. For example, are they influenced by neuromodulators, or by feedback from other networks? We’ll use genetic tools to answer those questions.

Furthermore, we think that plasticity is not just happening in one part of the brain, but it's distributed across many areas.

There's sort of a shared responsibility among brain regions for forming a memory. The idea is now to understand how these different brain areas are influencing each other, and how they alter local network function.

We also want to explore how these networks are influenced by disease, and, if can we train these networks to restore memory function.

A big task then.

That's a very big task, yeah.

Biography

Jan Gründemann's research seeks to understand which neuronal circuits and processing mechanisms in our brain are involved in sensory perception and memory formation using deep brain imaging techniques as well as methods for targeted modulation of neuronal activity. The goal of the research is the future application of the findings in neurodegenerative and psychiatric diseases. Jan Gründemann studied human biology at the University of Marburg and subsequently received his PhD from University College London. He is now leading the Neural Circuit Computations group at the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE) and is a professor at the Medical Faculty of the University of Bonn, Germany.