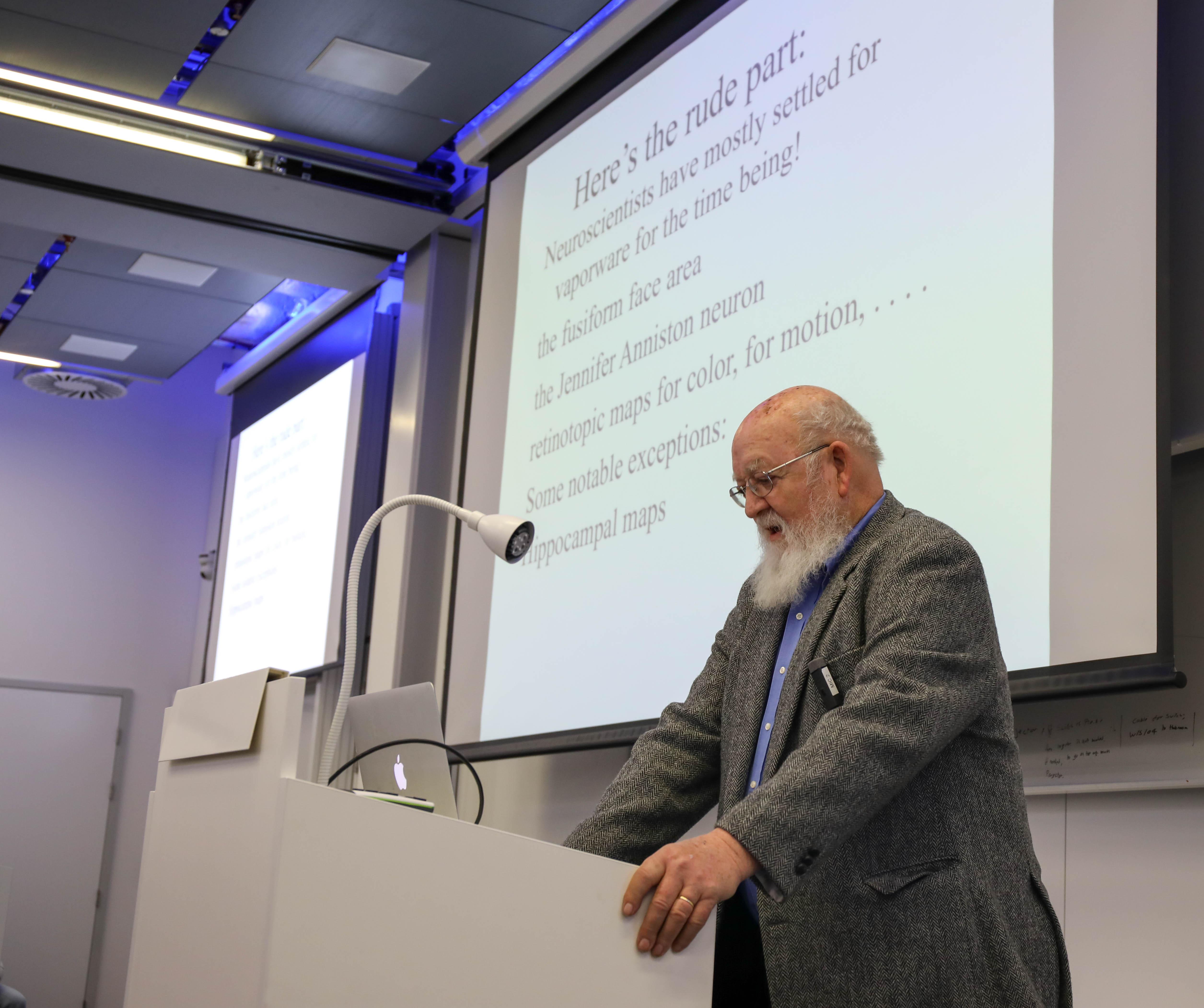

Tackling the hard questions of neuroscience

An interview with Professor Daniel Dennett, conducted by April Cashin-Garbutt, MA (Cantab)

What happens in the brain up to the moment of consciousness? This is a question that scientists and philosophers have pondered for centuries. But what if this specific formulation of the problem has hindered our progress? Professor Daniel Dennett, who delivered the SWC Public Lecture 2018, argues that we must also consider outcomes of this brain activity, asking the hard question, “and then what happens?” In the following interview, Professor Dennett outlines his views on free will, consciousness and the future of artificial intelligence.

How do you define free will?

Free will has nothing to do with physics, determinism, or indeterminism; it has to do with control.

Free will is the moral competence of an autonomous agent, but there are many degrees of autonomy. People are currently working on developing an autonomous driving car, but it won’t be completely autonomous. The car will be very much a slave. However, we can imagine an autonomous car, which could decide that it didn’t want to drive people around, and instead do something else.

In essence, free will is a social construct, but it is perfectly real. Free will is as real as money, for money wouldn’t exist if there weren’t a deep and well established pattern of consensus about what money was and the same is true of free will.

I like to think of having free will as being a member of the moral agents club. Small children and animals don’t have it, because you can’t move them with reasons. You can’t persuade them, you can’t explain to them why they shouldn’t do things, whereas you can with a responsible adult.

If you are the kind of agent that can take advice, and plan ahead, and imagine consequences, that’s all part of this moral competence. So, free will is not one thing, it is a whole lot of things, but, it coalesces around the idea that we are responsible. We can respond to the importunings of reasons that are presented to us.

Is free will purely an illusion?

Only if money is purely an illusion and there is a certain sense in which it is. After all, most of the euros and dollars are just virtual. We can think of money as a user illusion. Paper money and coins are simply crutches for the imagination.

I wouldn’t be surprised if there are people at the moment who are anxious about money going digital and electronic, and the vanishing of cash. They might think there is no money anymore and that we are living in an illusion, but that’s no more illusory than the value of a pound sterling in the first place.

So, if free will is an illusion, it is a very benign user illusion, in the same way that money is.

You have referred to the hard question of consciousness. How does this differ from the hard problem of consciousness?

They are completely different. The hard problem was coined by David Chalmers and it is basically the problem of qualia. According to Chalmers, the hard problem is how to explain that extra something that is consciousness. This is independent of what he calls the easy problems in consciousness, which are all about control and cognition and memory and so forth.

Here is a way of getting at what is wrong with the hard problem. Imagine we have two human beings, one of them is a conscious human being, and the other is his zombie twin, indistinguishable by any physical or behavioural test from the first human, but just not conscious (“there’s nobody home”). Suppose we have the conscious person and the zombie twin together in a room, spinning in a mad embrace and the lights go out. When the lights come back on, how do we tell which one is the zombie, and which one is conscious? By definition, there is no way to test this—and both of them think they are conscious!

Now, that’s not a hard problem, that’s a ridiculously impossible problem. There is a property that makes no testable difference and if it makes no testable difference, what makes you think there’s such a property? The trouble is that the hard problem has been defined in such a way as to be insoluble, but then we have every right to question the assumptions that go behind it.

Consider another example. Imagine a new theory of the internal combustion engine that states there are five invisible gremlins inside each cylinder. The gremlins don’t weigh anything, they exert no force, they don’t cast shadows, but they are present. Now, ask yourself, is this a serious theory? Clearly not.

But what is the difference between the gremlin theory and the theory of a difference between a conscious agent and a philosophical zombie? After all, the zombie agent thinks it is conscious as, by definition, it must be behaviourally indistinguishable from a normal human being.

By contrast, the hard question is about asking “and then what happens?” One thought experiment I’m currently working on to help to see the shape of the hard question is about a military drone. Imagine a drone that is being teleoperated by a human. Now think of the task of uploading all of the operator’s control powers and decisions to the drone itself, thereby making it autonomous.

What steps would you take to achieve this and what order would you do them in? What would you have to put on board the drone so when you cut the puppet strings, the drone became autonomous? This is a way of getting rid of the homunculus in the Cartesian theatre, by taking the homunculus apart and recomposing it, in essence composing the inner witness.

How can the hard question be dismantled piece by piece? Will a scientific revolution be required?

No scientific revolution is required and we are already dismantling the hard question piece by piece through neuroscientific research around the world including at the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre.

How do you explain the origin of consciousness from an evolutionary perspective?

Human consciousness differs in degree from the consciousness of other species. What really makes the biggest difference is language.

The way language makes a difference is that all the higher-level systems of control that determine the choices and behaviours of animals can do their work unmonitored. There is a competition for which behaviour will be in charge at any moment in time and one behaviour wins. But aside from the fact that the animal thereupon does whatever behaviour wins, there is no role for a further monitor of that to see how well it’s doing, and to reflect on it.

What would oblige the creation of such a role? The ability to give and take advice, would oblige this role and animals don’t do that.

Human consciousness is a user illusion. For whom? Well, in the first instance, for other people. It is what a mother uses to understand and advise her infant and then, when an infant grows up, it discovers that it cannot just influence others, it can influence itself. To do this, it has to start paying attention to what it is doing and why, in a way that other animals don’t.

Consciousness is the huge repertoire of higher level noticing. We don’t just notice things, we notice that we notice things and then we think about the fact that we’ve noticed those noticings. And it’s that indefinitely repeatable tower of recursive reflections that’s the hallmark of human consciousness, and there’s no sign of it exhibited by the behaviour of other species.

What behaviour would you expect to see in other species if they were conscious?

A well-known phrase, usually seen as the rueful observation of a foolish person, is “Well it seemed like a good idea at the time.” Any agent that can say this and mean it must have episodic memory for how it seemed at the time. This is a memory of an evaluation and it is the capacity to evaluate that evaluation in retrospect, and use that evaluation to reconsider and recalibrate its own policies. This is actually an extremely intelligent thing to be able to do.

There is regret in rats, according to a recent article, but it is not spelled out in the rat the way it can be spelled out in us.

What do you think the future holds for artificial intelligence?

I think that deep learning is extraordinarily powerful, but it is not going to solve some of the main problems that face us in cognitive science because it is not the right kind of architecture. The systems are, in a certain sense, completely parasitic; they don’t set their own goals, their own explorations.

For example, Watson is a brilliant piece of work, but it is entirely parasitic on the human comprehension that is embodied in the patterns to be found in all the text that is on the internet. It can’t engage in what you might call “novel problem solving”. It can do something a little bit like that, but it is a pattern finder tool.

An old tradition in AI is to put a premium on showmanship. Turing, who is one of my all-time heroes, unfortunately put a premium on fooling people into thinking you are an agent like them in his description of the imitation game. This has deflected AI from goals it should have had in unfortunate ways.

Should we be worried about AI?

We should be plenty worried about AI, but not for the reasons that people say. It is not that AI agents are going to overwhelm us, but instead we are going to overestimate their comprehension, and give them more authority over our decisions than they deserve.

Why do you think people often misinterpret your views on consciousness?

Some people are just so sure they know what consciousness is that they simply think I must be out of my mind, because in their view I am denying the very existence of consciousness. I’m saying consciousness is real, it just isn’t what you think it is.

The trouble is philosophers love to define things, and then live or die by the definitions they’ve endorsed. People end up talking past each other, or proving things about irrelevant artificial divisions of the world.

This happens in other fields, as well. Take the example of the engineer’s proof that bumblebees can’t fly. The aeronautical engineer in question used the proof as a reduction ad absurdum. He was showing what was wrong with the understanding of the aerodynamics of the day, because if that had been all you needed then he could prove that bumblebees couldn’t fly, which manifestly they can.

I think that definitions are overrated. Few biologists are comfortable if they are asked to define life. There is no really good reason for them to have a counterexample-proof, rock solid definition of what life is. We know some things are living, and some things aren’t, and then there’s all the intermediate things like viruses, spores and so forth. Where do you draw the line? Don’t.

Can you recommend any brain hacks?

When I am really stuck and baffled by an issue, I sit down at my desk and remind myself of the raw materials of the problem and then I go do something else.

When I had a farm, I used to go out and plough a field, or mow some hay, or paint a barn door, mow the grass, some relatively cognitively undemanding repetitive task, which would let my mind wander, but not just daydream, not just fall asleep. I’m alert, but I have elbow room to think at the same time. Going for a walk is a great way of shaking up your thoughts.

I suspect that when we know more about it, we will see that this has precisely the effect of temporarily adjusting all sorts of thresholds and dispositions that are blocking paths that are preventing you from making progress.

My colleague, Marcel Kinsbourne, likes to say, “The reason any problem is hard is because there’s an easy and tempting answer that’s wrong, and getting beyond that seductive error is the hard part.”

About Professor Daniel Dennett

Daniel is an American philosopher, writer, and cognitive scientist whose research centres on the philosophy of mind, philosophy of science, and philosophy of biology, particularly as those fields relate to evolutionary biology and cognitive science. Since publishing his landmark thesis Content and Consciousness in 1969, he has been a key voice connecting empirical and theoretical work in neuroscience and artificial intelligence to a materialist philosophy of mind. Daniel argues that while libertarian free will is an illusion we have some “elbow room” in our experience of freedom. His most recent book is From Bacteria to Bach and Back, a continuation of his physical conception of consciousness imaged through an evolutionary lens.