Finding the brain’s “real” tuning curves: a SIMPL approach

By April Cashin-Garbutt

Place cells are known for forming part of the brain’s “inner GPS”. These neurons, located in the hippocampus, fire when an animal enters a specific location. But what happens when an animal just thinks of a location, rather than physically visits the spot?

This presents a significant challenge for neuroscientists trying to plot tuning curves to analyse spiking data. As instead of simply plotting the frequency of a neuron firing against the animal’s position, they must consider how the neuron’s firing rate corresponds to the position the animal is imagining, its so-called “latent” position.

This challenge captivated Tom George, a PhD student at the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre, who was determined to help find a way to trace the brain’s “real” tuning curves. Working with colleagues across SWC, the Gatsby Computational Neuroscience Unit and UCL, the team developed a new method called SIMPL.

A common problem

We often think of locations without physically visiting them. For example, when you last planned a route, you likely imagined your destined location based on your memory or knowledge of the place. Animals do this too and it creates a challenge for researchers analysing spiking data.

“Many neuroscientists plot tuning curves to visualise the activity of hippocampal neurons against an animal’s position. But mismatches occur between where the animal is and the location the animal is thinking of. This blurs and distorts the tuning curves that we plot. And so, we wanted to find a way to undo this so that we can analyse the correct tuning curves without this distortion. The hope was that this might tell us more about the mechanisms of flexible spatial behaviour,” explained Tom George, SWC PhD student and first author on the paper.

To help solve this problem, the researchers decided to blend two techniques to analysing spiking data. In addition to using tuning curves, they turned to an alternative approach called latent variable models. This method involves taking lots of very high dimensional spiking data and compressing it to a very low dimensional space.

“We wanted to try blend the two techniques to get the best of both,” commented Tom George.

Introducing SIMPL

The blending of the tuning curve and latent variable model approach led to a new neural data analysis method called SIMPL – Scalable and Iterative Maximisation of Population-coded Latents.

This new technique involves iteratively refining the estimate of a latent variable in a fast and scalable way. Starting with the tuning curve of each neuron as a function of the position of the animal, the method uses the tuning curves to decode the apparent position of the animal. The new decoded behaviour can then be used to fit tuning curves, and the new tuning curves can be used to re-decode behaviour. Repeating this process quickly converges on the true latent space.

“By iterating this technique, we increasingly find better and better estimates of the position the animal was actually thinking of. Thus, we find better and better estimates of the tuning curves that actually generated these spikes in the brain,” explained Tom George.

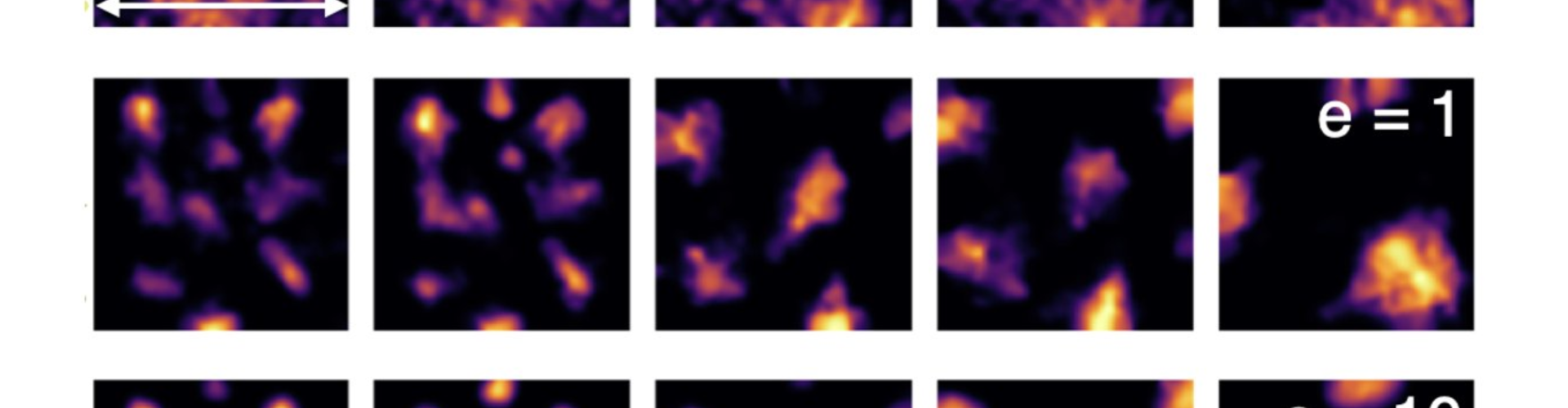

The animal is thinking of the green location but located at the yellow. Spikes plotted against green give sharp grid fields but against yellow are blurred. In the brain this discrepancy will be caused by replay, planning, uncertainty and more. This artificial data was generated using the RatInABox package.

Exploiting behaviour as an initial condition

One novel aspect of the SIMPL technique is that it exploits behaviour as an initial condition. This is different to other latent variable models, which tend to either not use behaviour at all or use it in a different way.

“The very first estimate of position that SIMPL uses to fit the tuning curves is the actual position of the animal itself. This is really important because behaviour is a good first-order explanation for what causes these neurons to spike. Because we have such a good initial condition, optimisation is quite straightforward,” explained Tom George.

Iteratively refitting and decoding from place field tuning curves converged on their true latent form.

Another novel aspect of SIMPL is that it can be run on a standard laptop and does not require a powerful graphics processing unit (GPU). This makes it available to those without access to high-performance computing resources.

Putting SIMPL to the test

To measure the accuracy of SIMPL, the team tested the technique on synthetic data sets, where the correct answer was known. They found that SIMPL performed better than all the comparable techniques that they tried it against both in terms of accuracy and speed.

To explore the mathematical reason why SIMPL works, Tom collaborated with Pierre Glaser from the Gatsby Computational Neuroscience Unit which is located within the same build as SWC. Together they showed that the SIMPL is very similar to a family of optimisation algorithms called expectation maximisation.

SIMPL use cases

While the main goal of the team has been to test the tool and make it available to other neuroscientists, they have also been applying the tool in their own research. For example, they have used SIMPL on hippocampal data sets, collected in Caswell Barry’s group at UCL, from rats exploring very large open field environments.

By applying SIMPL they found that “real” place fields are much smaller, sharper, more numerous and more uniformly-distributed that previously thought. The size of their receptive fields shrunk by over 30%, which was a sizeable refinement on the place field.

“We also wanted to see if SIMPL worked outside the spatial navigation domain, and we have now confirmed that it works on both hippocampal and non-hippocampal data. We ran the same analysis technique on a motor task data set and found optimised latent variables and tuning curves to explain the data,” commented Tom George.

The team hope that fellow neuroscientists will use SIMPL to analyse neural data; the optimised tuning curves it finds are much more closely linked to the “true” processes going on in the brain.

Next steps for SIMPL

In the future the team hope to explore the potential implications of SIMPL for brain-machine interfaces (BMIs).

“When you’re building a BMI, you want a way to rapidly decode what the brain is thinking of while a human or animal performs a task. Because SIMPL is very fast and efficient, we may be able to use it in an online setting so we can decode to the correct latent and get a more accurate readout of what the animal is thinking of during experiments,” concluded Tom George.

About SIMPL

To find out more about SIMPL:

- Read the paper, SIMPL: Scalable and hassle-free optimisation of neural representations from behaviour

- Access SIMPL code and data on GitHub, SIMPL

- Find out more at the thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations: ICLR 2025